By Melissa Dolan, LL’08, middle school humanities teacher and advisor, The Rivers School (MA)

In Kate Wade’s recent article about the power of youth voice, she urged educators to “Let the young people in your world take over, re-design and re-think the systems in place, disrupt the status quo.” So how do educators ensure our students have the tools to do this? Over the past few years of teaching an interdisciplinary civics course to 8th graders in an increasingly challenging national political climate, I’ve tried out a few ideas. Here are a few things I’ve found effective that you can try, too:

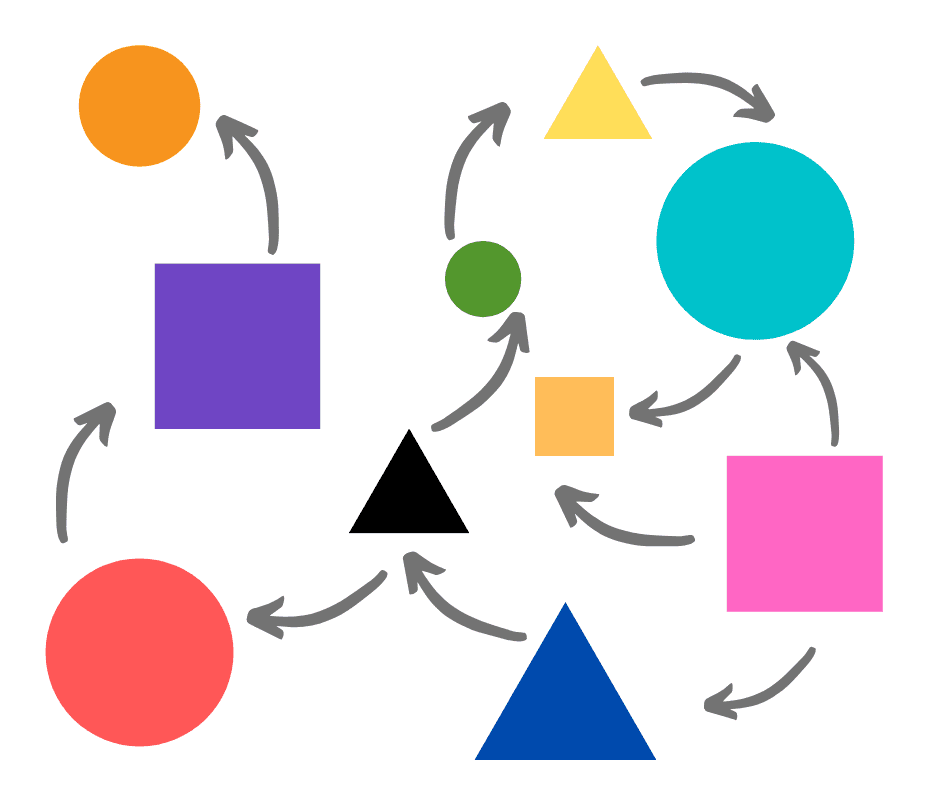

Teach students to analyze systems.

To re-design and rethink systems, students first have to recognize and understand them. Agency by Design, a research initiative out of Project Zero, offers systems thinking routines that can be applied to any discipline and are particularly accessible for middle school students. These routines help students move away from the binary thinking that is so often seen in the larger national discourse. Understanding systems allows students to see how individuals are shaped by the systems they inhabit and to see the power individuals have to make changes within those systems. After seeing the possibilities with these thinking routines, I restructured the course I teach by placing systems thinking at the core; while the content remained similar, the theme was changed from “Human Rights” to “Systems of Justice and Injustice.”

Re-design existing projects.

We end the year with an extensive independent project. Students are asked to: identify an issue and generate a clear research question for a current problem related to questions of justice in the United States; research multiple perspectives, the history of the issue, and the political or social impacts; map out the systems involved in the issue; and finally, based on the systems map, develop, design, and potentially take action on a solution. In addition to the systems analysis framework provided by Agency by Design, the structure of this project was also inspired by Educating for Global Competence: Preparing Our Youth To Engage the World by Veronica Boix Mansilla and Anthony Jackson.

Make space for student voice and choice.

The way in which we structured the project made a huge difference in terms of the depth of student engagement and understanding. Even before implementing systems thinking, we had always ended the year with a comprehensive project. Students worked in groups and had three weeks to choose and research an issue. At the end of each year, I’d always hoped for more depth– more engagement– from students. I chalked it up to the timing and put most of the responsibility for the outcomes on the students themselves. Turns out, the issue wasn’t them; it was me. More specifically, it was how I’d designed the project. The following year, I decided to seek out students’ interest in topics before assigning groups. I figured I would then group students based on shared interests. After reading the questionnaires students had filled out, however, I encountered a wide array of thoughtful topic ideas. So many, in fact, that, at the last minute, I decided to make the project an individual endeavor.

“Build the Bridge As You Walk On It.”

Making a last-minute decision to change the plan was not something I was accustomed to doing at that point in my teaching career. I’d always wanted to know exactly how I was going to get from Point A to Point B and wouldn’t make a change until I had a solution to every planning dilemma. How was I going to manage twenty-five different topics? How would I assess the project? But given students’ ideas, I decided to see where it could go. There were a number of unexpected and innovative developments that emerged as the new project took shape over the following years by following Ron Heifitz’s advice to build the bridge as you walk across it– advice I was grateful to absorb during my time at the gcLi Leadership Lab. One of the takeaways I valued most from the project was realizing that when students pursue something that matters to them, it doesn’t matter that you don’t have every answer about how to manage each nuance of the project; their intrinsic motivation carried them through the process.

“To Lead Is To Live Dangerously”

It is one thing to embrace the idea of leaning into discomfort. It is a whole other thing to embrace the reality of it. Once students began engaging in more depth with potentially controversial issues, I had a crisis of confidence. I started to doubt that I had the skills to facilitate the conversations. I started to worry. What if a student says something problematic and I don’t respond effectively? What if parents raise concerns? I shared these questions with my supervisor at the time. On my way out of her office, I turned to her and, half-jokingly on both points, said, “I’ll either turn this into a signature feature of our program, or I’ll get fired.” Without a moment of hesitation, she responded in a serious tone, “If you’re not operating in that spot as an educator on a regular basis, you are not doing your job.” I think of these words on a daily basis and have come to rely upon them as the foundation of this unpredictable work. They echo Heifitz’s wisdom that to lead is to live dangerously. On days when it might be easier to retreat to old teaching approaches, I remind myself that if we want the next generation of problem-solvers to be more successful than this one, we have to do our part to chart a new course.

Melissa Dolan loves the new perspectives her students bring to the subject matter every year. She hopes students leave her classroom with the motivation to wrestle with complexity and the understanding that they have the power to make positive change in the world around them. Melissa has been teaching middle school humanities at The Rivers School in Weston, Massachusetts for fifteen years. In addition to her teaching responsibilities, she serves as the middle school curriculum leader, a role that allows her to support the innovation of her creative, thoughtful colleagues.